- Home

- Marion Meade

Madame Blavatsky Page 2

Madame Blavatsky Read online

Page 2

Apart from Princess Katherine, whose fame lay in the dubious distinction of having failed to reach the throne, the achievements the Dolgorukovs had always centered on the male side of the line. But by the nineteenth century the energies of the men seemed to have lapsed into comparative sluggishness, and whatever prestige the family could boast of was to be found only on the female side, a fact of some relevance in the life of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky.

In the 1830s, Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope, the Englishwoman who roved the world dressed as a man, remarked about her travels in Russia:

In that barbarian land I met an outstanding woman-scientist, who would have been famous in Europe, but who is completely underestimated due to her misfortune of being born on the shores of the Volga River, where there was none to recognize her scientific value.3

Not withstanding Lady Stanhope’s British chauvinism and her mistake about the woman’s birthplace, the scientist had not been totally unrecognized. Princess Helena Pavlovna Dolgorukova, H.P.B.’s maternal grandmother, would have been an unusual person in any nation or century. A noted botanist, a scholar who spoke five languages fluently, an excellent artist, she possessed endowments rare for a woman of her time. Even more unusual was the fact that she succeeded in exercising her talents. While natural science was her chief interest, she was also proficient in archaeology and numismatics, and during her lifetime accumulated valuable collections in these areas. For many years she carried on correspondence with European scientists, among them geologist Sir Roderick Murchison, who founded the Royal Geographic Society. A fossil shell, the Venus-Fadeef, was named in her honor.

The roots of Princess Helena’s scientific interests are unclear. Her father, Prince Paul Dolgorukov, had little interest in orthodox science. On the contrary, he spent most of his time on his estate at Rzishchevo, in the Province of Kiev, addicted to his library of works on alchemy and magic, and was considered somewhat odd by his neighbors.

Having been born into an atmosphere of privilege and blessed with outstanding intelligence, it was the misfortune of the Princess to have an irregular family life. Her mother, Henrietta, was of French descent. A beauty with a reputation for flightiness, she married Prince Paul in 1787, produced two daughters in less than two years, and promptly abandoned him, leaving her infants behind. Twenty years later, shortly before Henrietta’s death, she returned to her husband, but by that time Princess Helena was well past the age when she might have benefited from a mother’s nurturing.

At the advanced age of twenty-four, the Princess opposed her father by expressing her intent to marry a young man her own age, Andrey Mihailovich Fadeyev. Fadeyev was a bright, ambitious fellow, as much in love with Helena as she was with him, but he happened to be a commoner—a fact of considerable importance to her father, Prince Paul, but of none whatever to his daughter. Eventually the Prince relented, and the marriage took place in 1813. Their first child, Helena Andreyevna, the mother of H. P. Blavatsky, was born the following year.

After the birth of Helena Andreyevna, the Fadeyevs moved to Ekaterinoslav, a Southern Russian city on the Dnieper River now called Dnepropetrovsk, where Andrey joined the Czar’s bureaucracy as an officer in the Foreign Department of Immigration. Ekaterinoslav, in the words of a German visitor, seemed “partly like a portion of a great plan not completed, and partly like a town which has fallen from its former greatness.”4 Originally founded by Catherine the Great as a summer residence, it was abandoned, along with other royal retreats, when she began to concentrate her architectural efforts on Tsarskoe Selo, near St. Petersburg. In the meantime, however, her lover Prince Gregory Potemkin had already laid out wide boulevards, built a palace which in luxury and Oriental splendor surpassed anything then known in Russia, and created a magnificent park stretching along the rocky banks of the Dnieper. A city planned on a gigantic scale, built to accommodate a million souls, it was actually inhabited by only a few thousand.

By the time of the Fadeyevs’ arrival, Catherine’s palace had fallen into ruins and, due to sand deposits, the Dnieper was navigable for only six weeks in the spring. In this provincial town, the Princess pursued her scientific studies and raised her daughter. Hers was an unusually happy marriage and the family was close knit. She had little taste for social calls on her neighbors, although apparently she responded cordially when they came to her. She paid no attention at all to fashionable modes of child-rearing. Generally Russian parents of the upper classes had little contact with their offspring, beyond morning and evening greetings, but the Princess, despite a retinue of serfs, refused to hand over her daughter to the care of nurses. Later, in a story which may be considered autobiographical, her daughter would write: “If I had to tell you that our mother was our nourisher, our caretaker, our teacher, and our guardian-angel, that, still, would not describe all her sacrificial, endless, selfless attachment, by which she constantly gladdened our lives.” Remembering Princess Helena’s own motherless childhood, it is unnecessary to look further for an explanation of her passionate attachment to her firstborn, Helena Andreyevna, and later, to her younger children: Katherine, Rostislav, and finally Nadyezhda, who was born when the Princess was thirty-nine.

Until the age of thirteen, Helena Andreyevna was educated by her mother, under whose supervision she studied history, language and literature. An ardent reader, she became a great admirer of French, German and Russian writers, whom she read in their own languages. Books induced in her visible emotional reactions. She could be found laughing and weeping over their pages. At an early age, she mastered the techniques of poetical composition and struggled to write her own verse, although at times she found this form of expression inadequate. “The thoughts would rush to her brain, powerless to be expressed in mere words, which only impeded their powerful and invisible flight, and she had to impatiently throw aside her impotent pen.”

A graceful, dreamy girl, delicate in health and indulged by her mother, she found plenty in books to fuel her imagination. She had a tendency to measure the heroic figures and settings of literature against her own surroundings: the barren steppes stretching on all sides to the horizon, the dry, blackish-gray soil with its parched grass and thistles, Ekaterinoslav itself with its unsophisticated residents. “My attention,” she recalled, “was taken up by historical events, by the aspirations, passions and actions of outstanding people who have contributed to the spiritual elevation of mankind.” In comparison, her everyday life “looked pale and insignificant as an ant-hill.”

Determinedly intellectual, she held herself aloof from the other young ladies of Ekaterinoslav, whose interests and goals were more commonplace. “I reached with my mind everywhere,” she later said of herself as she had been at fifteen. “I felt with my heart everything.” There is a portrait of Helena Andreyevna, whose date is unknown but appears to be from the period of her teens. Her dark hair is pulled back smoothly behind the ears and curled under; the filmy white gown, tight at the elbows in the current fashion, reveals a slim, childish figure; and around her neck is knotted, somewhat rakishly, a small scarf. The perfect oval face, with its button mouth and dreamy eyes, gives an impression of elegant hauteur. It is a pretty face, evidently composed demurely for the portrait, but it fails to give the smallest indication of the banked fires smoldering beneath the surface.

She had her share of admirers among the young men of the town, and would have had more if she had not clung to her impossibly lofty expectations about men. No doubt influenced by her parents’ loving relationship, she was also affected by her reading, and she fantasized herself the heroine of a romantic literary tale in which love and marriage were synonymous. As a result, she nourished dreams about “the possibility of eternal changeless love between two people.” There was nothing abstract about this conviction: “I had profound faith in it, I hoped for it, I waited for its realization, lovingly carrying in my heart the germ of the sacred fire.” Her love would be reserved for someone special: “I did not waste any of its sacred flame on temporary infatuati

ons. No—I guarded it as a celestial gift, which I hoped would bring me happiness once and forever.”5 Such was the idealistic concept on which she planned to base her marriage.

At sixteen, she encountered Captain Peter Alexeyeivich von Hahn of the horse artillery. Recently decorated in the Turkish Campaign6, von Hahn was twice her age, well educated, good-looking and charming, with the splendid masculinity that could be found among uniformed officers of Czar Nicholas’s regiments. That Helena felt dazzled by this heroic visitor is easily understandable. The captain, who was not based permanently in Ekaterinoslav, was immediately smitten by the refined Helena and set about courting her in the manner of a man who knows how to charm and amuse an inexperienced young woman.

For a person addicted to plumbing the depths of her own emotions, Helena Andreyevna does not seem to have submitted the dashing Captain von Hahn to a thorough examination. Swept away, she evidently had no clear sense that marriage would mean leaving home and following the army from one barracks and backwater town to the next, many far worse than Ekaterinoslav. The power of physical attraction prevailed and when he proposed, she enthusiastically accepted.

There is no record of von Hahn’s feelings. However, he does not seem to have been an unusually sensitive man, and it would not be unfair to surmise that he, like any other professional soldier, failed to take women seriously. If he noticed at all that Helena Andreyevna’s view of men was foggy with illusions, he must have dismissed it as girlish romanticism that she would soon outgrow.

Von Hahn’s pedigree seemed sufficiently impressive for a daughter of a Dolgorukov. His solidly military family was descended from an old Mecklenburg family—the Counts Hahn von Rotternstern-Hahn, one branch of which had migrated to Russia a century earlier. Peter’s father, Alexis Gustavovich von Hahn, was a well-known general in the army of Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov and had won a decisive battle in the Swiss Alps. For a time he had been commandant of the city of Zurich. Peter von Hahn’s mother had been a countess before her marriage; one of his brothers was Postmaster General of St. Petersburg; and other members of the family were sprinkled in high positions throughout the army and civilian government.7

It is not surprising that Princess Helena, despite a natural reluctance to part with her favorite child, should have reacted favorably to her daughter’s choice of a mate. The couple was married toward the end of 1830, and by Christmas, Helena Andreyevna was pregnant.

A thousand miles to the north of Ekaterinoslav, at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Czar Nicholas I was seething with frustration—if a man known for his outward detachment could be described as seething. More than six feet tall, utterly humorless, he ruled with an iron rod the fifty-five million souls— nearly half of them slaves—who populated an immense empire that stretched from eastern Poland to the Pacific Ocean. Once, in a letter to Empress Alexandra, he protested, “I am not your salvation, as you say. Our salvation is over there yonder where we shall all be admitted to rest from the tribulations of life.”8 Yet to his subjects, the thirty-four-year-old monarch appeared only slightly less awesome than the Almighty, a fact of which Nicholas was all too clearly aware.

Despite his philosophic acceptance of life’s inevitable pain, Nicholas was gripped by alarm in 1830. Europe, in his opinion, had gone mad. Earlier that year he had been outraged by the French revolution, which had overthrown Bourbon King Charles X in favor of Louis Philippe. The kindest words he could find for the usurper were “traitor” and “scoundrel.” In what seemed to him an epidemic, a revolution in Belgium had won that country its independence from the Netherlands. Now, on the heels of these ominous events, Nicholas was forced to contend with a major insurrection in his own domain. A man who struck people as autocracy personified, he was deeply worried and, although he had once lamented, “I was born to suffer,” the “Iron Czar” did not welcome needless aggravation.

Among the peoples who Nicholas detested, such as Jews, Greeks, and Poles, the Poles had stood first on the list since their 1829 assassination attempt during his coronation in Warsaw. To be sure, the Poles had no reason to love him: in 1795 the kingdom of Poland had been partitioned between Russia, Austria and Prussia and its name erased from the map of Europe in one stroke. Token moves to do something for the unfortunate Poles had been attempted by Napoleon, and even by Nicholas’s elder brother, Alexander I, who had given his eastern slice of Poland a constitution and a parliament. Nevertheless, rumbles of discontent persisted.

On November 29, 1830, a military revolt erupted in Warsaw. It was sparked by student cadets at the officers’ training school, who murdered several senior officers loyal to the Russian government. Army regiments and masses of civilians were quick to join the uprising. The Russian viceroy and commander-in-chief, Nicholas’s brother Grand Duke Constantine, did nothing to stanch the momentum and within weeks the Russian army was forced to flee the country. At first, Nicholas observed helplessly. But by January 1831, in a belated move to grab back his lost property, he began mobilizing troops and shipping them to the Polish border. Peter von Hahn’s battery was among them.

During these unforeseen events, Helena Andreyevna returned home with her family. She continued her studies as before, but now she was pregnant. In addition to her fear that Peter might be killed in combat, she had another anxiety: a cholera epidemic of serious proportions broke out that winter, accounting for more deaths among the regiments than the Poles. Grand Duke Constantine was its most notable victim.

This was an interlude of national terror that did not confine itself to any single area of the country. In villages and cities, among peasants and royal families, the disease swept away its victims with startling rapidity. At St. Petersburg, in the belief that the government was deliberately poisoning the water, citizens mobbed Haymarket Square. The Emperor, driving up in an open carriage, rose to his feet. “Wretches,” he screamed, “is this your gratitude? The Almighty looks down upon you. On your knees, wretched people, on your knees.”9 Ten thousand fell to the cobbles, crossed themselves, and went home, abandoning questions about the provisions he was making to check the epidemic.

In Ekaterinoslav, where the plague did not strike until summer, hardly a day went by without news of somebody dead or dying. Inevitably, tragedy knocked on the Fadeyevs’ door and a number of serfs fell ill. The disease began with convulsions, stomach pains and vomiting, and ended a few days later with coffins and funerals. Once cholera entered a house, it generally spread rapidly, making no distinction between servant and master.

It was in this morbid atmosphere that Helena Andreyevna gave birth to a premature child during the night between July 30 and 31, 1831.10 Not only did the infant girl arrive weeks ahead of schedule, but she appeared to be far from healthy. Plans were immediately made for baptism, lest she be carried off by natural causes or cholera with the burden of original sin on her soul. Hasty though the baptism may have been, it was conducted with all the customary paraphernalia of the Greek Orthodox ritual: lighted tapers, three pairs of godparents, participants and spectators standing with consecrated candles during the lengthy ceremony. In the center of the room stood the priest with his three assistants, all in golden robes and long hair, as well as the three pairs of sponsors and the household serfs.

In the first row behind the priest was the baby’s child-aunt, Princess Helena Pavlovna Dolgorukova’s three-year-old daughter, Nadyezhda. She must have grown weary of standing in the hot, overcrowded room for more than an hour and, unnoticed by the adults, had sat down on the floor and begun to play with her candle. As the ceremony drew to a close, while the sponsors symbolically renounced Satan by spitting three times at an invisible enemy, the flames of Nadyezhda’s candle lit the bottom of the priest’s robe. Nobody noticed until it was too late: the priest and several bystanders were severely burned.11 For this reason among others, it would be remarked that Helena Petrovna Blavatsky had been born under exceedingly bad omens. Indeed, according to the superstitious beliefs of orthodox Russia, she was doomed from that day

forward to a life of trouble and vicissitude.

In the short run, precisely the opposite seemed to be the case. The cholera infection died out in the Fadeyev household without having stricken a single member of the family, and as the summer of 1831 ended, the tide of war had already turned against Poland. However, it was not until the following summer that Peter von Hahn returned home to the bride he had left eighteen months earlier and the daughter he had never seen.

By eighteen, Helena Andreyevna von Hahn had plunged into married life with a man who was still virtually a stranger to her. Their first home was the small garrison town of Romankovo, whose single advantage was its proximity to the Fadeyevs. But just as Madame von Hahn was struggling to accustom herself to her new surroundings and friends, the captain was transferred to Oposhnya, a tiny community in the Province of Kiev. The stay in Oposhnya proved equally brief, and over the next two years there was a succession of further moves. During that time, Helena Andreyevna gave birth to her second child, a son named Alexander, nicknamed Sasha.

In the early years with Peter, Helena Andreyevna must have made an effort to adjust, but an army wife’s rootless mode of life was not to her taste. Russian cavalry officers, as a group, were known neither for their intellect nor even for their serious interest in military strategy. Trained to serve with blind obedience, they were not encouraged to display initiative, and most of them frittered away their time drinking and gambling. How closely Captain von Hahn fit into the general ambience is unknown, but his wife found the existence empty and unimaginative, and decried the boring dinner parties and the endless conversations about horses, dogs and guns. One imagines that these provincial towns were the sort Chekhov depicted in The Three Sisters and that like Masha, whose knowledge of three languages was an unnecessary luxury, Helena Andreyevna found she knew “a lot too much” to fit in.

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine Free Woman

Free Woman Unruly Life of Woody Allen

Unruly Life of Woody Allen Bobbed Hair and Bathtub Gin

Bobbed Hair and Bathtub Gin Madame Blavatsky

Madame Blavatsky Stealing Heaven

Stealing Heaven Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This?

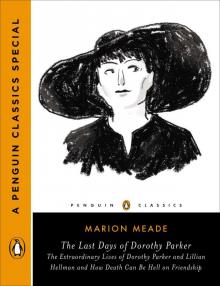

Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This? The Last Days of Dorothy Parker

The Last Days of Dorothy Parker